The do-everything wood that’s priced right

Ask a forester familiar with eastern hardwoods about yellow poplar, and he’ll talk about tuliptree. And when a New England architect specifies whitewood, he most likely means yellow poplar. Talk to a lumberman about yellow poplar, though, and you’ll both speak the same language because this tree represents the most valuable commercial species of the eastern forests.

Even before the first settlers arrived, New York’s Onondaga Indians were very familiar with “the white tree.” From its easily worked pale wood, they made canoes and utensils. When colonists arrived, the newcomers learned to craft what they soon called yellow poplar into everything from berry baskets and boxes to trim and furniture.

Today, the wood remains just as versatile. No other species can match yellow poplar’s variety of uses. It becomes construction lumber; moldings, plywood cores, drawer sides, matches, piano and organ actions, containers, paper, woodenware, furniture parts, and even caskets.

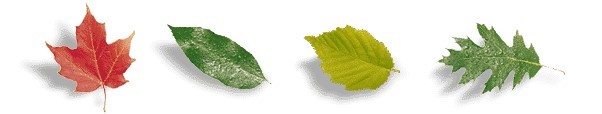

Wood identification

Yellow poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera) shares the family tree with magnolia. But because of its relatively softwood, a trait that resembles the true poplars like eastern cottonwood and the aspens, it long ago gained association with these trees.

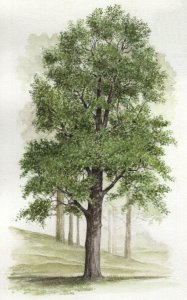

Growing to its greatest size in the southern Appalachian Mountains, yellow poplar reaches heights of 150′ and diameters greater than 8′. Frequently, these forest trees will be clear of branches for the first 80′ to 100′!

In its range, yellow poplar prefers to grow singly among pines and other hardwoods, rather than in pure stands. But you’ll have little trouble recognizing this tree. The sometimes 2″-thick, gray-brown bark of mature trees has deep furrows between its ridges. Summer brings yellow poplar’s greenish-yellow, tuliplike blooms among the tree’s glossy, saddle-shaped leaves. In winter, yellow poplar’s inedible, conical fruit remains on its branches.

At about 28 pounds per cubic foot dry, the wood of yellow poplar weighs two-thirds as much as black walnut. It’s also about half as strong and hard. However, the medium-textured wood is straight-grained.

Although the yellow poplar sapwood has a creamy tone, its heartwood ranges in color from tan to gold, often with streaks of blue, gray, and purple. These highlights make up for the wood’s otherwise plain grain.

Uses in woodworking

With strength sufficient for most projects, good stiffness, stability, and wear resistance, it can become furniture, trim, toys, and cabinets. For bowls and treenware, it carries no odor or taste. Unless you’re going to paint your project, though, limit yellow poplar’s use to indoors.

AvailabiIity

Abundant throughout its eastern range, yellow poplar becomes less available farther west. Where you find it, expect widths up to 20″, thicknesses to 3″ or more, lengths to 16′, even when surfaced. Only lumber is sold.

Some woodworkers prefer the often striking colors of yellow poplar’s heartwood. (Deep blue or purple streaks indicate mineral stains, a coloration that does not harm the wood.) If you prefer less colorful variation in your stock, specify sapwood or pick through the boards at your supplier for those of uniform tone.

Machining methods

Yellow poplar means good news if you like to work wood with hand tools (or would like to learn). It’s kind to cutting edges, bits, and abrasives, so you can have some real fun project-building. But if power tools are your approach, keep the techniques in the box below in mind, and the following tips:

- Although yellow poplar isn’t as hard as many other woods, it does have a tendency to burn. Use only sharp cutting edges.

- You also can avoid burning by keeping the stock (or the tool) moving at a constant rate. To hesitate allows the cutter to heat up enough to burn.

- Drilling hardwoods usually requires a slower rpm than drilling softwoods. With yellow poplar’s tendency to burn, however, you’ll want to speed up the process. And in thick wood, or with large-diameter bits, raise the bit occasionally to clear chips from the hole.

- Yellow poplar is a good wood on which to practice your hand-planing skills. With a finely honed cutter, it planes nearly as smooth as glass. Sanding produces equally fine results.

- In joining, the wood holds nails and screws quite well, and it takes all types of glues.

- Staining poses about the only finishing problem you’ll have with yellow poplar. As its name implies, the wood does have a yellow (and sometimes green) cast. And the possible color variations in heartwood make results unpredictable unless you first test the stain on scrapwood of the same tone. Clear finishes may require a toner to balance the differing colors of the wood surfaces.

- Yellow poplar rates as about the most paintable wood around, especially with enamels. Water-based paints and clear finishes tend to raise a slight fuzz. A primer, followed by light sanding before the finish coat, will still produce a great look.

Carving comments

The straight, even-grained wood of medium density won’t threaten even beginning carvers. In fact, it’s only a little harder than bass-wood, and holds details well. Note the finishing comments above though.

Turning tips

Whether you scrape or shear, yellow poplar shouldn’t cause you any problems on the lathe. It’s great for functional bowls.

SHOP-TESTED TECHNIQUES THAT ALWAYS WORK

Any exceptions and special tips pertaining to this issue’s featured wood species appear under headings elsewhere on this page.

- For stability in use, always work wood with a maximum moisture content of 8 percent.

- Feed straight-grained wood into planer knives at a 90° angle. To avoid tearing, feed wood with figured or twisted grain at a slight angle (about 15°), and take shallow cuts of about 1/32″.

- For clean cuts, rip with a rip-profile blade that has 24-32 teeth. Smooth cross-cutting requires at least a 40-tooth blade.

- Avoid drilling with twist drills. They tend to wander and cause breakout. Use a backing board under the workpiece.

- Drill pilot holes for screws.

- Rout with sharp, preferably carbide-tipped, bits and take shallow passes to avoid burning.

- Carving hardwoods generally means shallow gouge bevels—15° to 20°—and shallow cuts.