The weatherproof stock of Old Ironsides, barrels, and mission furniture

When England sought wood to rebuild her once-great naval fleet, eyes turned to the American colonies’ forests of white oak because by the 1700s, English oaks had all been felled. British ship-builders, though, scorned New World oak as inferior.

Proud American builders knew better, and built ships of native timber. The famed frigate Constitution, known as Old Ironsides, had a gun deck of Massachusetts white oak, a keel from New Jersey white oak, and frame and planks from magnificent Maryland trees.

As New England sea captains went on to sail their all-American, white-oak ships to the far corners of the world, another growing industry also made far-reaching use of the wood. Ever since colonial times, coopers had hand-riven staves of white oak for barrels. And as the young nation’s merchant fleet increasingly sailed the seas, it carried with it more and more cooperage for export trade. Some of it was bound for France’s vineyards, or to the West Indies for barreling rum and molasses.

Later, during the Victorian Age of the late 1800s, still another use emerged—as a fine firrniture wood. Stained and highly varnished, it was sold as Golden Oak, and attained a popularity that persisted through the mission furniture of the 1920s. Today, even though somewhat revived for furniture and cabinets, white oak represents less than one fifth of all oak—red and white—harvested in the U.S.

Wood identification

Although you can find dozens of species of white oak growing nearly everywhere in the U.S., the grandest of them all is Quercus alba. Called stave oak and fork-leaf white oak, the tree can grow to ponderous size within its range. Trees more than 8′ in diameter and over 150′ tall have been recorded. Usually, the trees fall between a 3-4′ diameter and an 80-100′ height.

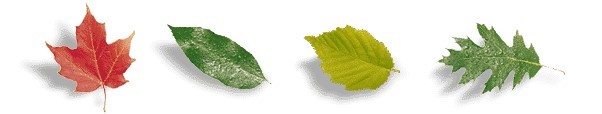

You can easily identity white oak by its round-lobed leaves (red-oak leaves have sharply pointed lobes). In the absence of leaves, check for white oak’s tell-tale light, ash-gray bark with its scaly plates. Or, look for acorns. Those of the white oak have a shallow cap with an inside that’s satiny smooth. The red-oak acorn cap is hairy inside.

Uses in woodworking

Unlike red oak, white oak resists moisture and decay, making it ideal for outdoor furniture and boats. Indoors, it’s a cabinet-class wood for tables and chairs, floors and trim, and turnings. Basketmakers also rely on the green wood. But, due to its hardness, carvers aren’t fond of it.

AvailabiIity

The lumber industry lumps all white oaks together, so you may not always be getting Quercus alba. Don’t worry, all species share the same wood traits.

Widely available at hardwood suppliers.

White oak requires careful handling during the drying process to ensure boards free from seasoning defects, such as internal honey combing, so closely check any questionable boards before you buy. You also might inquire about the source of the wood. Slower-grown wood from the Appalachians and the north offers an easier-to-work texture than that from southern bottomlands, although they may look the same.

Machining methods

White oak’s hardness requires power tools, but it shouldn’t give you any problems as long as you keep the following in mind:

- Because white oak dulls cutting edges, use carbide-tipped cutters and saw blades.

- The wood’s straight grain presents only moderate resistance to ripping, but its hardness demands a slow feed rate.

- White oak also has a greater tendency to splinter than red oak. That means that you should take a few shallow passes on the planer or jointer when removing stock.

- When routing white oak, especially end grain, also take’ shallow passes. And be sure to use a back ing board on cross-grain cuts for splinter- and chip-free machining.

- In counterboring, only quarter-sawed or rift-cut white oak presents a problem. The eye-appealing rays may lift or chip out, so work slowly. This hardwood also requires slower speeds (about 500 rpm or less) on the drill press.

- Again, the wood’s hardness requires sanding with progressively finer grits. And don’t attempt to orbit-sand this species because swirl marks are hard to remove.

- White oak’s high tannic acid, when used for outdoor projects, will turn ordinary screws black and stain the wood. Although they cost more, use brass or stainless steel fasteners for long-lasting good looks. And always predrill white oak for fasteners.

- Don’t use casein glue with white oak. Its components react with the high tannic acid content of the wood and the bond won’t properly adhere.

- White oak responds to all stains and finishes well, and unlike open-grained red oak, there’s no need to fill for smoothness.

Carving comments

Armed with a mallet and very sharp gouges (or power-carving tools), only determined carvers tackle white oak. One tip: Grind cutting edges to a deep bevel of 25°-30°for roughing in. For the shallower, shaving cuts of detail work, return to 15°-20° bevel.

Turning tips

- For turning between centers, avoid splintering by entering the wood with a sharp, clean-cutting tool, such as a skew, and take shallow cuts.

- Sharpen your turning tools more frequently when working white oak so that they never abrade the wood.

SHOP-TESTED TECHNIQUES THAT ALWAYS WORK

Any exceptions—and tips pertaining to this issue’s featured wood species—appear under headings elsewhere on this page.

- For stability in use, always work wood with a maximum moisture content of 8 percent.

- Feed straight-grained wood into planer knives at a 90° angle. To avoid tearing, feed wood with figured or twisted grain at a slight angle (about 15°), and take shallow cuts of about 1/32″.

- For clean cuts, rip with a rip-profile blade that has 24-32 teeth. Smooth cross-cutting requires at least a 40-tooth blade.

- Avoid drilling with twist drills. They tend to wander and cause breakout. Use a backing board under the workpiece.

- Drill pilot holes for screws.

- Rout with sharp, preferably carbide-tipped, bits and take shallow passes to avoid burning.

- Carving hardwoods generally means shallow gouge bevels—15° to 20°—and shallow cuts.