The Pacific Northwest’s most abundant hardwood

Just as a connoisseur of Eastern ham insists that it be smoked only with hickory, the salmon fisherman of the Pacific Northwest demands his fish be cooked over alder coals. That’s entirely fitting to this tree that prefers living close to water.

As the most abundant hardwood species of the region, red alder has for a century been the seafood industry’s choice for smoking fish. And loggers who daily fell the mighty Douglas fir prefer the heat of a winter fire fueled by red alder. Until recent years, these were the wood’s primary commercial uses in a land ruled by lumber-producing conifers.

In fact, red alder was pretty much dismissed for production because, like a weed, the species popped up in clearings where other trees were felled. Burnt-over tracts also were quickly covered by young alder stands, often threatening more commercially important softwood seedlings. Today, loggers look to the red alder to supply a growing market along the West Coast, in Asia, and in Europe for furniture wood.

Wood identification

Red alder (Alnus rubra) grows best in moist conditions at lower elevations throughout its range. The greatest volume occurs around Washington’s Puget Sound and in Northwest Oregon, where trees may reach heights of 120′ and diameters of 36″.

At first glance, you might mistake red alder for aspen or paper birch because the tree has light gray bark with dark mottling. Older specimens in damp growing conditions feature dark spots of moss. Red alder’s leaves also remind you of a birch’s, yet they are nearly twice as long, with a furry underside. In the fall, they drop to the ground still green.

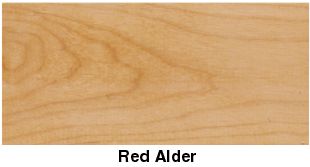

The wood of red alder, at 28 lbs. per cubic foot dry, weighs about one third less than red oak. The heartwood and sapwood are both a rich reddish brown with straight, close grain. When red alder is cut in the autumn, the wood color is frequently a golden yellow. Freshly cut logs may stain if not processed within a few weeks after harvest.

Uses in woodworking

Red alder makes excellent core stock for plywood because of its stability and good gluing properties. Also, it’s commercially used on the West Coast for production turnings, cabinets, paneling, doors, millwork, unfinished furniture (especially chairs) and waterbed frames. Because it has a close grain and readily accepts stain, red alder can imitate cherry, mahogany, and even walnut. But because it tends to be somewhat softer than these woods, you should avoid using it for tabletops and other projects that take abuse. And always use it indoors; the wood isn’t durable.

AvailabiIity

Due to increasing demand for commercial use, red alder prices on the West Coast actually are competitive with the cost of many Eastern hardwoods of its caliber.

You may be able to buy red alder at retail hardwood outlets in the Midwest. But in the eastern U.S., hardwood species such as yellow poplar and red gum beat its price.

If you plan to order red alder from a small sawmill or operator be sure to specify normal, uniform color. Although red alder may be about the easiest North American hardwood to dry, it does require a special kiln schedule that avoids discoloration through the oxidation of extractives. This oxidation frequently results in mottling. By introducing steam in the kiln drying, skilled operators can produce colors that range from yellow to dark red, a technique that can enhance the final finishing if red alder is to be substituted for costlier stock. Once you have your red alder, you’ll want to keep the following tips in mind.

Machining methods

Although you can work red alder easily with hand and power tools the wood does have a tendency to blunt cutting edges. So keep sharp ones handy or resharpen for high-quality cuts.

- Ripping poses no problems with red alder because of its even texture. Crosscutting does require a backing board to reduce any possible tearout.

- If you experience tearout when planing, either reduce the feed rate or adjust the wood to a slight (15°) angle to the cutterheads.

- For routing, slow the feed rate for smoother cuts.

- All adhesives work well with red alder without special preparation of the mating surfaces.

- Red alder is known in the wood products industry for its nail-and-screw holding power. But, predrill for screw holes to lessen the chance of splitting.

- Red alder tends to fuzz just a trace during sanding, but unlike rock-hard sugar maple, it won’t retain the scratches left behind should you skip a grit.

- Because of its color consistency and pore structure, red alder takes all types of stains equally well without sealing or otherwise conditioning the wood.

- You can use any type of clear finish on red alder. It also holds paint extremely well.

Carving comments

- An even texture, straight grain, and relative softness (similar to butternut) makes red alder easy to carve with both hand and power tools.

- With only subtle figure, this is a wood you’ll want to try for naturally finished relief carvings as well as three-dimensional carvings destined for paint or stain.

Turning tips

Be sure to use sharp turning tools to avoid tearout, otherwise expect red alder to turn with the ease of cherry, only softer.

SHOP-TESTED TECHNIQUES THAT ALWAYS WORK

Any exceptions, and special tips pertaining to this featured wood species, appear under bold-faced headings elsewhere on this page. But for all wood species, always practice the following.

- For stability in projects meant for indoor use, work only wood with a maximum moisture content of 8 percent.

- Feed straight-grained wood into planer knives at a 90° angle. To avoid tearing, feed figured or twisted grain at a slight angle (about 15°), and take shallow cuts of about 1/32″.

- For clean cuts, rip with a rip-profile blade having 24-32 teeth. Smooth cross-cutting requires at least a 40-tooth blade.

- Avoid using standard twist-drill bits. They tend to wander in the wood and cause breakout. Use brad-point bits and a backing board under the workpiece.

- Drill pilot holes for screws.

- Rout with sharp, preferably carbide-tipped, bits and take shallow passes to avoid burning.

- Carving hardwoods means fairly shallow gouge bevels—15° or more—and shallower cuts.