The West’s mountain-climbing conifer

If ever a tree loved to live in the mountains, it’s the western white pine. You’ll find it getting along quite happily in the high country of California, Idaho, Montana, Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia.

Given western white pine’s preference for altitude, it may seem strange that this species ranks among the most important timber trees of North America. The tree’s size and wood quality make the extra logging effort worthwhile. Even Scottish explorer and botanist David Douglas, who discovered the western white pine on the slopes of Washington’s Mt. St. Helens back in 1825, thought it important to send some seeds to his homeland. Today, the products of those seeds grow majestically in the highlands of Scotland and Ireland.

Commercially, western white pine commands one of the highest prices of all softwoods. It’s in continued demand for window and door frames, molding, and high-quality veneer for plywood.

Wood identification

Western white pine (Pinus monticola) thrives in the deep porous soils of north-facing mountain slopes where the snow gets deep and the growing season stays short. That’s why northern Idaho produces about two-thirds of the U.S. supply. In the industry, it’s even called Idaho white pine.

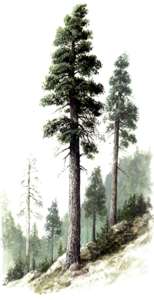

Despite the rigors of climate, specimens reach 175′ in height with diameters of 8′ at breast height. The silvery-gray trunks of mature forest trees usually have no branches for half or more of their height.

Unlike its eastern cousin, which has a crown of widely spreading branches, western white pine has a short-branched, narrow, yet symmetrical crown. But, like eastern white pine, the pale, bluish-green needles of western white pine grow in bunches of five. Slender, slightly curved cones grow to a length of about 12″.

Under each scale of the cone lie two tiny seeds. In September and October the cones ripen and open to shed them.

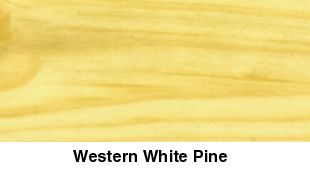

The straw-colored wood of Western white pine weighs 26 pounds per cubic foot air-dry, and in strength and hardness compares with Douglas fir. Straight grain and even texture means that it works easily. The choicest western white pine boards come from Idaho and carry the grade stamp IWP, for Idaho White Pine.

Uses in woodworking

Besides millwork, you can use western white pine for indoor furniture, cabinets, and shelving units, as well as light construction. For carving, it is somewhat harder than eastern white pine, but holds detail equally well. You also can turn the wood.

AvailabiIity

You should find the better grades of western white pine (Choice & Better, and Quality) in the board section of home centers and lumberyards. Boards should have the stamp mark MC-15, meaning that they have been kiln-dried to 15 percent moisture content or less.

The boards you buy may carry the additional « IWP » grade-stamp imprint. If so, you’ll have some of the best pine available, with very few knots. But western mills don’t kiln-dry softwoods to a low moisture content of 8 percent that you typically find in hardwoods. By industry standards, your pine may have as much as 12–15 percent moisture, which is okay if you let the wood acclimate in your home for a week or so to stabilize it before using. Then, you’ll want to keep the following tips in mind when working western white pine.

Machining methods

Although pines are considered softwoods, some species are harder than others. And that’s the case with western white pine. The wood rates as 30 percent harder than eastern white pine, and although you can successfully work it with hand or power tools, be sure you keep all tool cutting edges sharp.

- Unlike many other species of pine, western white pine boards have little pitch in them to build up on your saw blade. Still, it does occur, so avoid the burning and blade wander that accompanies gum buildup by using a Teflon-coated blade or occasionally cleaning the blade with steel wool dampened with acetone.

- This wood doesn’t splinter easily, but a backing board helps reduce the chance when routing across the grain.

- Due to the hardness of western white pine, you’ll want to drill pilot holes for screws.

- The better grades of western white pine will only have small, tight knots known as « pin knots. » They won’t fall out, but to prevent bleed-through, you should seal them with shellac before applying a clear or painted finish.

- If you plan to stain the wood, first put on a sealer coat of wood conditioner or diluted shellac (cut 50 percent with denatured alcohol) to prevent unevenness of the stain color.

Carving comments

- The hardness of western white pine doesn’t vary from earlywood to latewood as with other pines or firs. This even texture means the wood will take detail without chipping or splintering.

- For sculptural carvings, pin knots may add character since the wood is otherwise featureless. But be sure to seal them.

Turning tips

Thick stock blanks of western white pine may contain pitch pockets deep inside. If the pockets haven’t dried, droplets of pitch can appear on a freshly turned surface. Just scrape them off after they harden, then finish the wood.

SHOP-TESTED TECHNIQUES THAT ALWAYS WORK

Any exceptions—and tips pertaining to this issue’s featured wood species—appear under other headings you’ll find elsewhere on this page.

- For stability in use, always work wood with a maximum moisture content of 8 percent.

- Feed straight-grained wood into planer knives at a 90° angle. To avoid tearing, feed wood with figured or twisted grain at a slight angle (about 15°), and take shallow cuts of about 1/32″.

- For clean cuts, rip with a rip-profile blade that has 24-32 teeth. Smooth cross-cutting requires at least a 40-tooth blade.

- Avoid using common twist drills in woodworking. They tend to wander in the wood and cause breakout. Use brad-point bits and a backing board under the workpiece to reduce tearout.

- Drill pilot holes for screws.

- Rout with sharp, preferably carbide-tipped, bits and take shallow passes to avoid burning.

- Carving softwoods generally means using fairly steep gouge bevels—20° or more—and taking deeper cuts.